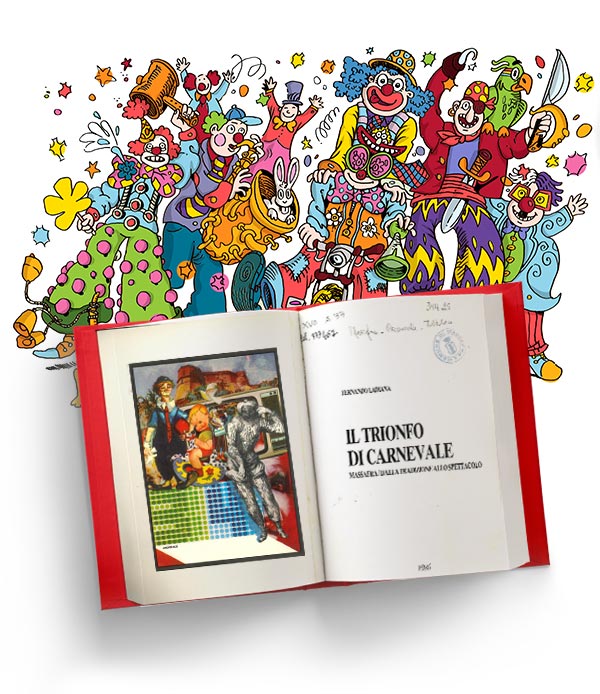

L’autore: Fernando Ladiana

![]()

Fernando Ladiana, journalist and teacher, born and raised in Massafra, was Honorary Inspector of the Superintendence of Artistic, Environmental, Historical, Archaeological and Archival Heritage, as well as author of: Heirs without History, Massafra and the Great War, The Stone of Hunger, The Triumph of the Carnival, The guide of Massafra.

Do you like this book? Come to the library and read it!

File e tesse la Quarantèle

Doppe ch’è muorte Carnevale

Pe Campè li sette file

pure de notte tesse e fileNu taradduzze la settemane

sazzie tutte li cristiane

disce ‘zi prevete chiù muorte ca mbise

tuzze forte e ‘nghiane suseLa mascenele aggire atturne

la chenocchie ‘ngrosse allu fuse

chiange e suspire la Quarantele

pe la morte di CarnevaleA lengua strascenute

cercate perdone a Dije

attachete ‘nganne na psare

e gire ngunicchiete li sette vie.

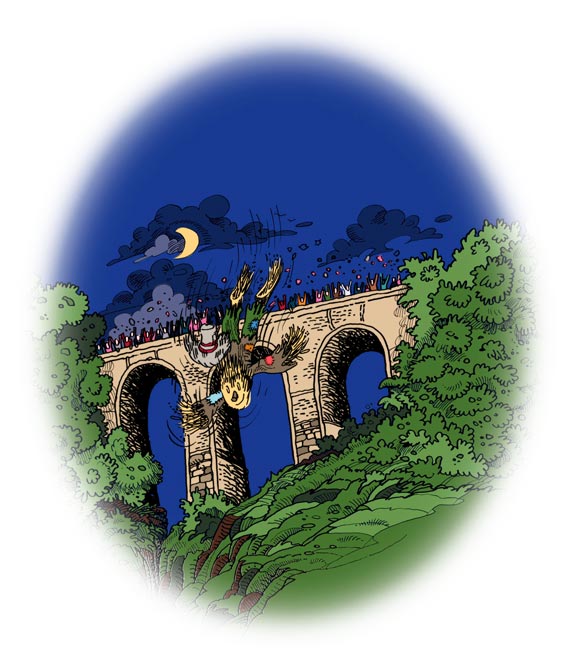

At midnight, the straw puppet was burned in the square or thrown from the bridge into the ravine, while the sacristan of the nearby Church of Santa Maria mournfully, tolled the main bell, as if to say “go, the Carnival is over!”

The Tradition

“Pasqua e Natale addò t’acchie, Carnevale fall’a caste”

“Pasqua e Natale addò t’acchie, Carnevale fall’a caste”

In Massafra, this saying has always been abided by, so much so that in the past, our farmers, who once spent the winter months in Calabria and Lucania for the pruning of olive trees, returned to the family, giving themselves at least a three-day break.

The Legend of the Shepherd of Massafra

A popular legend, linked to the origins of our local Carnival, narrates the tale of a shepherd who could never leave the large farm, where he was employed as the guardian of the flock. During the day, he was always with the animals as they grazed and at night, he would sleep with the animals, stretched out on a bag of straw. He had no holidays, or days to rest.

Once the owner, out of strange generosity, decided to send him home for the Carnival Celebrations. The road was long and the poor man had to make the journey on foot, facing the harshness of a very cold and snowy winter. He carried an old saddlebag over his shoulder with a few kilos of broad beans, a bag of wheat, a flask of oil and one of wine, which represented the remainder of his salary, “paid” in kind, according to the custom of the time. While walking, he met a man also dressed as a shepherd, with a beard and long hair.

“Where are you going?” He asked the Shepherd.

The Shepherd answered “Home, for the Carnival Celebrations”

“But today is Monday and the celebration has ended”

“It does not matter” replied the shepherd “I will be happy to see my wife, my mother, my children and my village”.

“Go, go” said the stranger, whom the legend identifies as Jesus of Nazareth, “go and enjoy the family, but also the Carnival Celebrations”.

Arriving in the village, the shepherd learned that the Carnival had been extended by two days and that great preparations were underway for Tuesday to celebrate the “Holy” Carnival in a worthy manner. The shepherd enjoyed himself as he had never done before, but soon returned to his usual job, with the memory of the screams and the racket of the masks.

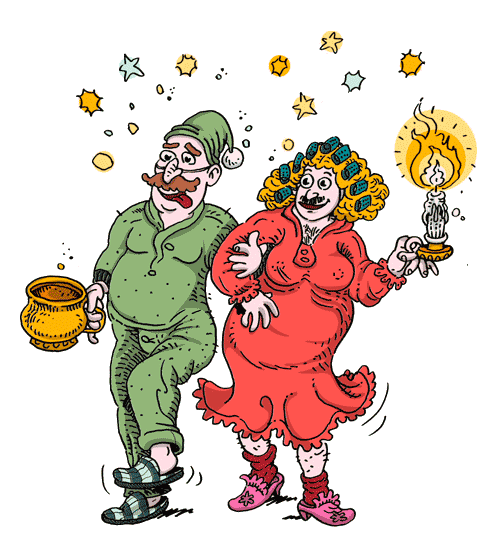

The personifications of the Carnival, in its ritual Massafresi representations are a drunkard pleasure-loving man and his wife dressed in mourning clothes, also represented with puppets.

The man is created with a straw puppet with a reaper’s hat, reed pipe, a small clay stove and a flask of wine. In the past, he was placed on a kitchen chair on the cornice of the house, especially if along the crossroads or a “local road”.

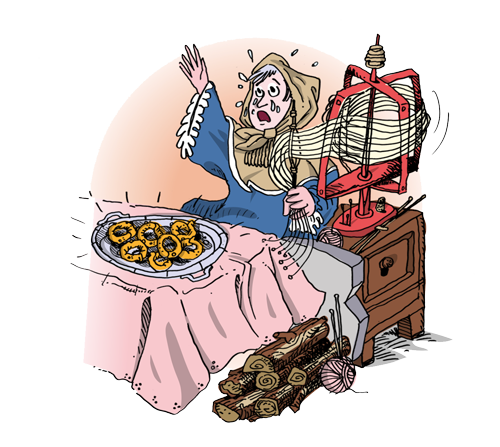

The Quarantana is considered the wife of Carnival and represents Lent. She is a puppet no more than 50 cm high, dressed as a spinner, with spindle and spinning wheel. On Ash Wednesday, she was hung between one house and another or arranged near the chimneys and well in view on the “lamie” (ancient temporary or permanent residences) with a faggot of wood and seven “tarallucci” (twisted ring shaped biscuit), symbolising the seven weeks of Lent.

Unlike many other areas (also southern areas of Italy), Carnival (the personification of Carnival made man) in Massafra did not undergo any “trial” nor was he killed, but died from overeating, which evidently caused indigestion.

One of the oldest popular representations of Carnival in Massafra was the “Procession of Sant’Accione”, organised by the “fleece weavers”, at the end of the last century who with other Carnival events enlivened those days.

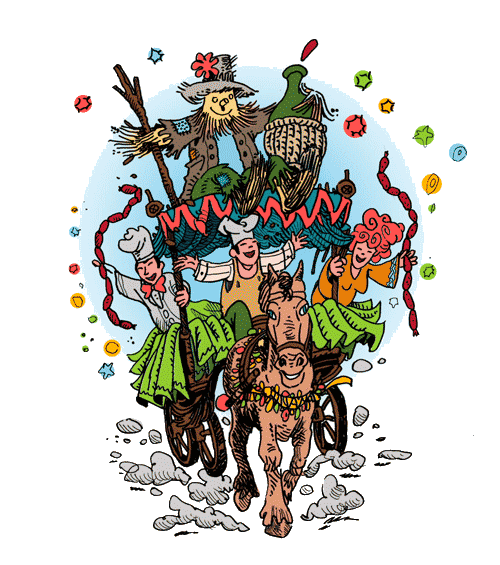

That of the Bakers, who every year, and always late on Sunday night, would carry a coffin around on their shoulders, or on a cart, with a puppet filled with straw and dressed in peasant clothes a representation of the death of the Carnival. The procession was preceded by an endless line of pretend brothers, who rang large cowbells, several priests with crosses and aspergillum, others with lit torches and “lampieri” types of lights. Rosa, his wife, walked behind the coffin, surrounded by sneering mourners and by the family members of the poor Carnival, who was normally called Giovanni, in memory of a certain Giovanni Carnevale, who lived in the first half of the nineteenth century, master of ceremonies of the first Carnival events

However, the interpretation which attributes to the killing of Carnival, the aim of eliminating and purifying sin and evil, remains valid also in this case. The two rituals were scripted in a procession and never on stage, precisely because it was necessary to involve as many people as possible along the way.

The myth of the “the land of plenty” has ancient origins in popular imagination; the fantastic depiction of the kingdom of Bengodi (imaginary kingdom were happiness and abundance reign),

“lakes of poured fat, mountains of cheese, rivers of milk or wine, houses of pecorino cheese and other good things”

A fabulous kingdom where nature was pleased to bestow its treasures, without man having to lift a finger. A myth that was certainly alive until modern age, in the 1700’s the kings of Naples every year had a fake “land of plenty” built in the square, it was all made of wood, with houses, gardens, shops with edible foodstuffs, fountains from which wine gushed, while lambs and pigs grazed among the houses. At the king’s signal, the people launched themselves to plunder the fantastic construction living a moment of illusory well-being.

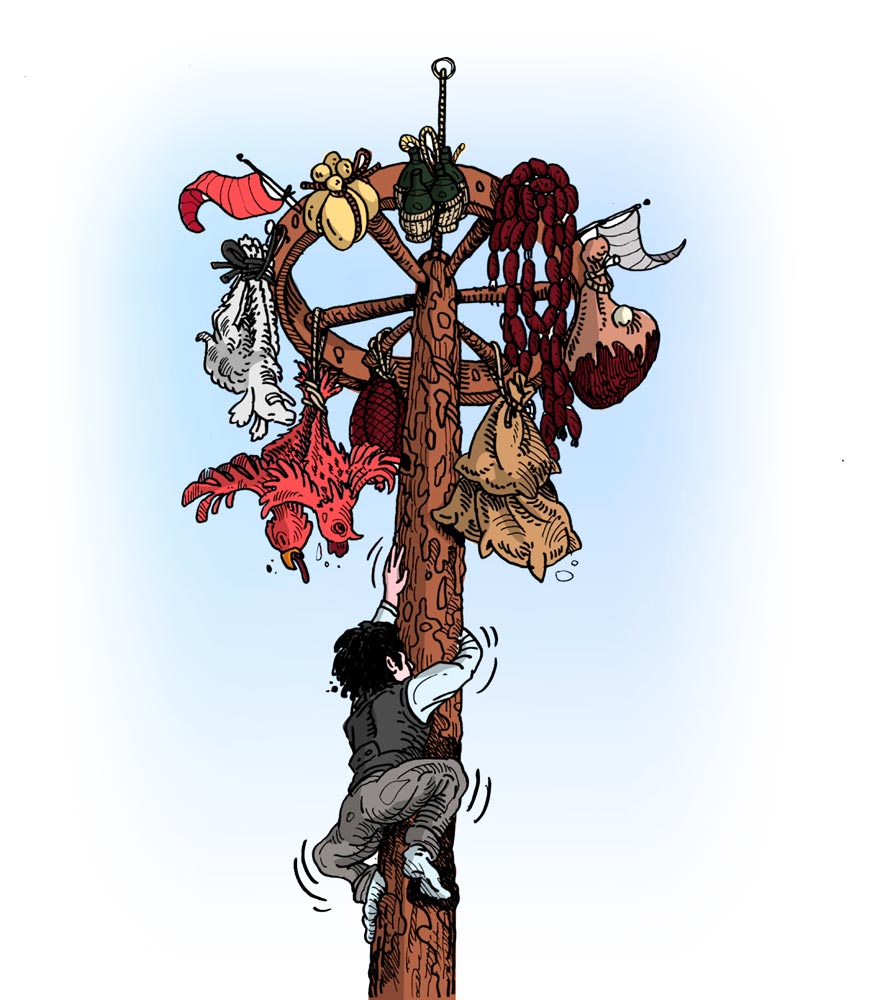

In Massafra the “tree of plenty”, was a wooden pole planted in the ground, six meters long and about twenty centimetres thick, greased with fat, at the top a wooden wheel was fixed that supported the prizes: a lamb, a turkey, two roosters, a few packs of pasta, slices of salted lard or tuna, fresh or dried sausage, “caciocavalli” (caciocavallo type of cheese) and several flasks of wine.

Carnival Thursday

Also known as, Cuckold Thursday was celebrated with a lavish lunch in the family, with a feast of “roasted sausages” sausages roasted on the grill and plenty of wine.

It was customary between monks and priests to celebrate their Thursdays, exchanging a cordial invitation to lunch, which was succulent and appetising during the Carnival period.

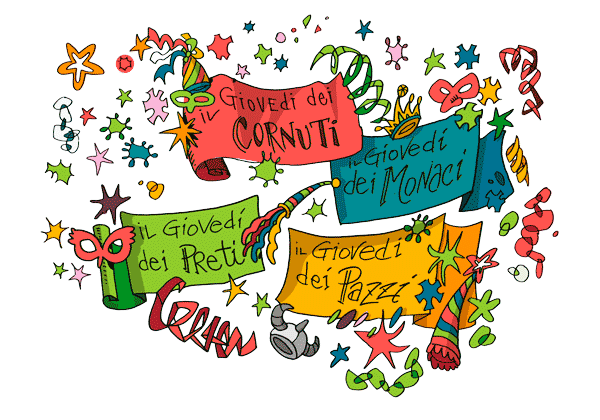

At the time, Carnival began on 17 January with a cycle of celebrations, which were mostly organised on Sundays and Thursdays. These had a name and a specific meaning “Monk Thursday”, “Priest Thursday”, “Cuckold Thursday” and last but not least “Crazy Thursday”.

On “Crazy Thursday”, the celebrations exploded in all its splendour in the squares, in the streets and in dark alleys. Young people came home from work a few hours earlier than usual, they disguised themselves as best they could, and imitating married couples, hunchbacks and cripples. The mask-holder and other friends made a circle singing: “Abballe Ciccantuòne, senza cante e senza suòne“, which translated means “Dance buffoon, without song and without music”.

Modern Carnival Chronicles

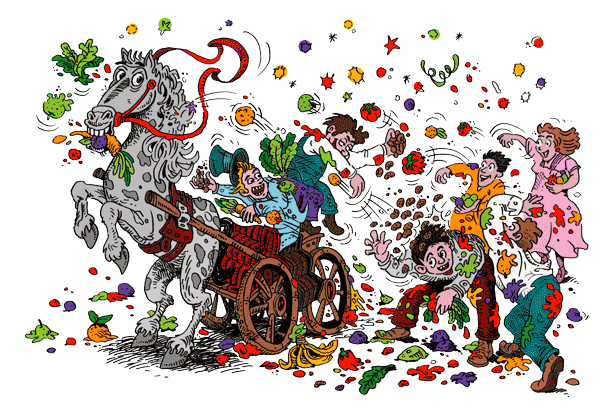

Between 1870 and 1920 on Shrove Tuesday afternoons, the Massafrese Carnival was characterised by the battle of the confetti.

The battle of confetti between gentlemen, in a carriage or gig, and bourgeois, on foot.

The gentlemen threw beans, the bourgeois unleashed oranges, lemons, bunches of lettuce and any other vegetable that was on display on the greengrocers tables, which were later compensated at high prices.

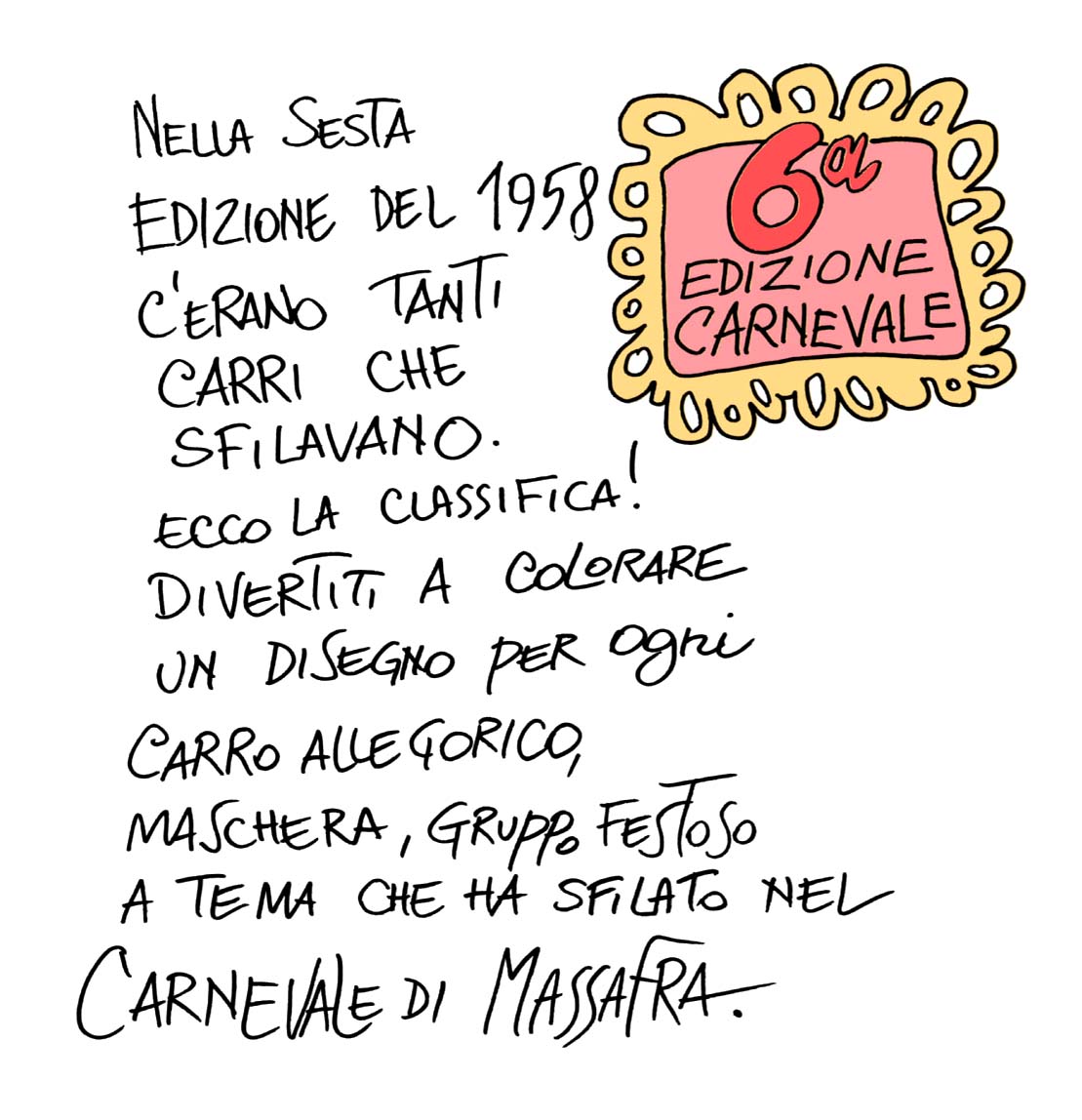

In 1950, the idea arose of restoring the Carnival celebration to the town. Indeed, on 21 February, the last Sunday of Carnival, there were only but a few masks to be seen, perhaps because people were still reluctant and awkward at these organised amusements.

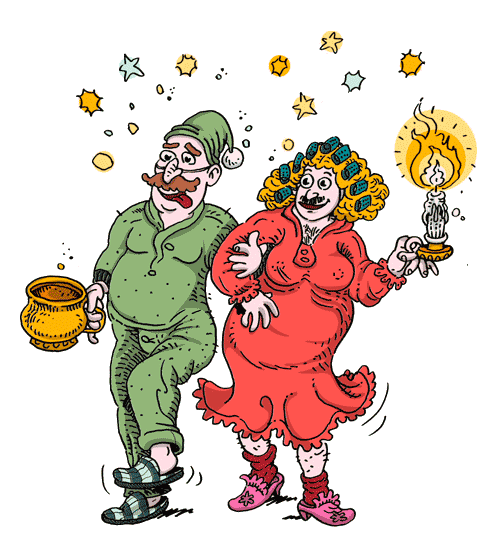

Cencio Vinci and Lello di Bello disguised themselves as an old couple in nightgowns: one with a night pot and the other with the candleholder. Very amusing as they mimicked the act of wanting to urinate in public.

Among the participants of the masked course of the fifth edition in 1957, the “Clown in the city” complex created by Mimino Benagiano that was very amusing for the characteristics found.

Play with the Massafra Carnival

Have you analysed the Triumph of the Carnival? Do you want to test yourself?

Try one of the games below!

Contact

Contact